We’re very interested in knowing about your artistic experiences as a child and as a teen.

As a child I drew lots of rockets and dinosaurs. (Now that I’m a parent I’m able to borrow my kids’ toys to paint: it’s like a second childhood!) I was interested in science and nature. I read science fiction. I wanted to be an astronaut or a zoologist. I drew a lot and was recognized as talented but took very little interest in Art. As my talent developed and I became interested in comics I thought I might become a comic strip artist. I remember being given a book of Michelangelo’s drawings and copying them, but adding futuristic space-suits and turning the figures into action-heroes. Then, when I was sixteen, I had a ‘road to Damascus’ moment and realised I wanted to be a painter. It seems funny looking back because I was very ignorant about art and particularly about the current state of painting and what was going on in the art colleges. But painting looked like the best way to test my talent. That’s how I looked at it back then: the game with the highest stakes.

At what age did you first begin oil painting on canvas? Were you encouraged to do so by teachers, or by family?

My first oil paintings were done when I was 17 and were portraits of my school friends. I already had a name for doing portraits in graphite or ink (often at the back of the class), and had lots of cooperative sitters. An older sister who’d been to art college gave me some help, but for the most part it was a case of jumping in and making a mess. They were messy! But they were painted from life and aimed to be truthful, so it was a good start, looking back.

Was I encouraged? Because ‘soft’ options like art were often set against ‘hard’ subjects like physics or economics at school (so you couldn’t do both) I was encouraged by my family to take the hard subjects and do the art in my own time, outside of school. So I didn’t spend much time in the art room. To be honest, I didn’t respect much of what went on there. Despite this I did have an art teacher who helped me put a portfolio together, and I was accepted for the art college in Dublin. My father expressed serious misgivings about painting as a career, but he didn’t try to dissuade me. Later on, after I’d left college, I had a crisis of confidence and decided to give up painting, but he talked me out of it. This was a great surprise: I thought he’d say “It’s not easy being a painter. You gave it a good try; move on”. Instead he did everything to try and keep me painting. Eventually I overcame my problems. So I owe him a lot.

What were some pivotal or seminal works that you saw that stayed with you, and informed your style?

Van Eyck’s ‘Virgin of Chancellor Rolin’ for its amazing perspective and depth of field. Giorgione’s ‘Concert Champetre’ for its arcadian vision. Titian’s ‘Sacred and Profane Love’ for its compositional perfection and gorgeous sensuality. Rembrandt’s self-portraits for their humanistic subtlety and depth. Courbet’s ‘Atelier du Peintre’ for showing that you can be convincingly realistic, modern and allegorical/mythological at the same time. These are a few of my favourites. In my early thirties I discovered Odd Nerdrum’s works and these had a major impact on me. Of all my painter-heroes he’s the only one I got to meet.

Regarding still life, which artists or individual works or periods inspire you?

Well, the Dutch were the great pioneers of still life (predictably enough since theirs was the first society to achieve modern standards of urban affluence and in which materialism and liberal capitalism were first expressed as a philosophy: still life to me is essentially an art of affluence and materialism). But I think Chardin is the greatest still life painter. I get tired of his homely, petit-bourgeois values but he is so much more painterly than any of the Dutch; light and atmosphere are more important than what he paints. It’s a different way of fighting matter. I’ve also admired the still lifes of de Heem, Goya, Manet, De Chirico, and Morandi.

Your ability to capture the light to dark is enviable. How did you master this? Are there certain techniques, or materials, crucial to it, or is it the person’s eye or painterly hand that is key?

It’s very much a matter of direct observation and transcription; working from life, setting the canvas close to the painted objects so that, looking at both, I can create an equivalence of visual effect. Standard ‘old-master’ techniques such as glazes and impasted highlights play a role. And experience. If you spend tens of thousands of hours doing something, you get good at it eventually!

We’re fond of your elements of surprise, such as the gorillas on your canvases. One (in “Monkey Painting”) is even wielding a camera.

Coming late to an old tradition like European painting, where there are so many classic images and there’s so little virgin territory to explore, it’s hard to avoid pastiche and staleness. So I try to find ways to stay true to the tradition and yet stretch it a little, to have a conversation with old and new elements. I depend on the viewer’s knowledge of the tradition: the element of surpirise you speak of only works where there are prior expectations. And I know I annoy viewers looking for the ‘timeless’, classic image. Sometimes I’m asked why I have to ‘ruin’ a picture by sticking a monkey in it. If it were done as a joke they’d be right, but my intention is serious. The ‘surprise’ is intended to effect a shock of recognition: that the viewer is not looking at an ‘Old Master’, but a picture of our time, expressing living issues and concerns. If the viewer shares these concerns the relationship between viewer and painting is altered; each becomes implicated in the other’s world. You might look on my traditionalism as a form of camouflage, a ‘trojan horse’ tactic that relies on our complacent veneration of ‘classic’ art to get past the usual intellectual defences; to reach and grab and hold the viewer where they least expect it.

Another image we simply couldn’t stop talking about is “Veiled” (2012). The surprise of the fruit in plastic bags causes a double-take, but what comes over us even more strongly is that feeling of death and life juxtaposed. Still life, as a death-life dichotomy. Can you tell us about your process in creating “Veiled” and also about its critical reception worldwide?

I think death is always implicated in still life at some level, and I often tackle it explicitly – but not in this one. It is interesting that you respond in this way, considering a painting of objects neither dead nor alive. (Is a pear or orange ‘alive’, properly speaking?) But the picture is constructed as a drama of light and darkness, and I suppose what is at stake in any drama is ‘life’.

When painting a picture like this I usually place the canvas close to the objects to be depicted, my aim being to transcribe as faithfully as possible the dynamic of light and colour in the original. In pursuing this dynamic I am pushed to utilise the entire tonal range from white to black and the entire chromatic range from neutral greys to the most intensely saturated colours, but these extremes within the picture remain bound together and controlled by the optical coherence of their relationships. The result, while strikingly forceful, I think remains naturalistic and harmonious.

For me chiaroscuro means much more than ‘light-and-shade’: I conceive it more literally as ‘clear-obscure’. Light itself is thus the agent of clarity, but in its encounter with air and matter it is deflected, scattered and obstructed in such complex ways that its revelation is always only partial and teasing. With the painted objects frontally lit, the transition from clarity to obscurity is also a journey from surface into depth, drawing us from the superficially self-evident towards uncertainty and darkness. The bags are painted quite texturally, with crisply impasted lights and something like a physical approximation of the thin plastic. What’s in the bags is barely indicated, but because the surface of the bag and the effect of light transmitted through it is so truthful, I think the viewer will tend to accept it as a convincing token of the riches contained within.

I believe the original marble bust is called ‘Veiled Lady’, circa 1860, by Raffaelle Monti (mine is a plaster copy). Sculptures of this sort have long been popular because they display such virtuosity in their surface effects. These effects are deployed in a complex, almost painterly way, using the play of light and shade over the form to create an illusion of translucency and of a surface beneath the surface. The veiled figure thus reinforces my reflection on painterly virtuosity and the play of surface against depth within the painting; a ‘doubling’ which emphasises that this play is not an accidental feature of the picture, but its principal theme. Placed centrally and facing the viewer, she is also a sort of mirror-image of the beholder, a reminder that for us perception is inevitably clouded, that our struggle to separate appearance from reality is never complete.

As for the painting’s ‘critical reception worldwide’, I don’t make headlines globally so this phrase looks hard to live up to, but what response there has been is positive and encouraging. It has featured in a couple of magazine articles on my work, it will be reproduced in a small book on still-life painting to be published shortly in the US, and it sold in San Francisco last year. Much more of my work is being exhibited and sold internationally now, which is a good sign.

You write exquisitely and in great depth about your work, for example, in your excellent interview for the magazine The Painting Imperative. Were you as a child or younger person a deep and abstract thinker? Or were these abilities something that developed through later study of art history and art philosophy?

I’m the youngest of a large family where questioning and debate were encouraged, and I’ve always had an interest in ‘big’ questions, but I think intellectually I matured quite slowly. It took me a long time to work out what was going on in the world and how I might fit in. When I was at art college I found it very difficult to express in words what I was doing in my work. I couldn’t even see that a verbal explanation was desirable. Could people not use their eyes and SEE what I was doing? I felt everything of importance was IN the picture, and words were superfluous. I think people who are very visual often don’t understand how much most people need language to help them navigate the world. It’s only by trial and error that I’ve discovered how important words are for preparing the critical reception of a painting. When you explain the whole process and intention behind a picture you dramatically alter how the work will be received.

I know some people feel that it’s a mistake to say too much about one’s own work for fear of undermining the painting’s mystique, and that the verbal packaging should be left to critics and professional wordsmiths operating at some distance from the work. I disagree. I now try to be as open as I can about my own intentions, and speak as plainly as I can about the whole process so as to dispell as much of the ‘mystery’ as possible.

In the interview for The Painting Imperative, you speak about the Faustian aspect of Western civilization, about “…its belief in matter, force and energy; its claims to mastery of nature; a will-to-power that recognises no limits, dreaming even of the ‘conquest of space’.” Your work often challenges these Faustian traditions and assumptions. But do you think that people who view your work understand its actual subversiveness?

I’ve no idea. I think a painting can withstand a lot of varied interpretation if the image is strong. I don’t even think I’m being subversive: I’m trying harness the power of the Faustian myth and expose its implications. If I succeed the work will articulate something that is deeply embedded in our culture and demand attention on that basis. But if an image becomes part of the common culture, it no longer belongs to the artist and his intentions hardly matter. Of course, I want to communicate and find common ground through my work; it’s a form of signalling. But I’m very aware of the limits of visual communication and realise that ‘success’ inevitably means that the images become pawns in other peoples’ games. Even where I write about my work, I’m not really trying to control how others understand the images; it’s more to show how much thought and labour goes in ‘behind the scenes’, and to demonstrate the kind of sympathetic thinking that might help unlock a picture.

You cover a lot of bases with your work, and we know still life is just a small part of what you do, but we’re curious, why paint still lifes? What about the genre or tradition of the genre is enticing to you?

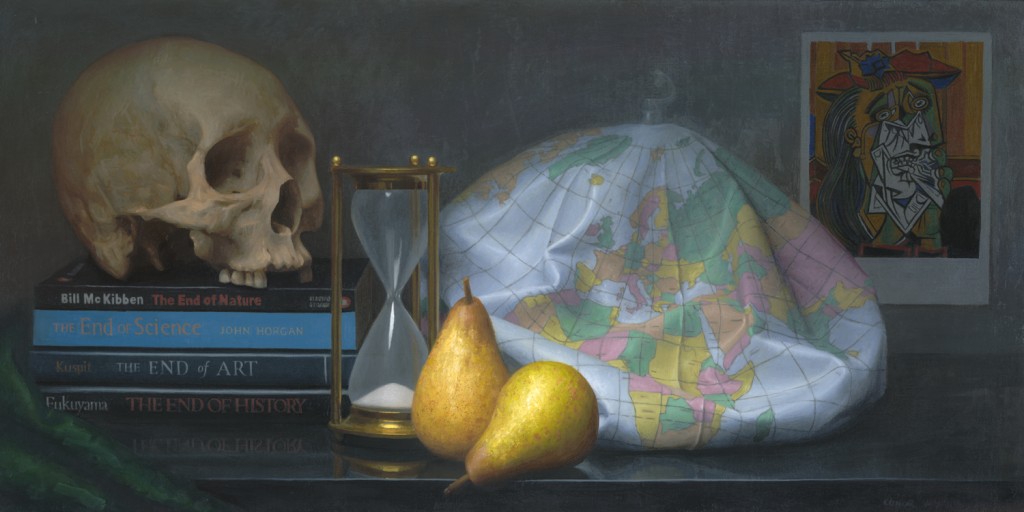

To begin with I was not really interested in the genre: my principal interest has always been painting people and ‘living nature’ rather than ‘nature mort’, but live models are expensive and I paint slowly, and still life seemed like a good way of producing small saleable works that I could paint from life and develop my eye and technique at the same time. But the deadness of objects, their lack of energy or any psychological presence has always been an obstacle to me, something to overcome. I’m not at all happy with still life as an exercise in pure objectivity or pure form. So I end up trying to treat the painting as a miniature drama, a microcosm. I use objects that have meaning for me and try to get the whole painting to make a statement, to express an attitude. And because still life is an art of objects – of deadness – attitudes like objectivity, materialism, fatalism, nihilism, are easily accessible through the genre. It’s a battleground for me: a way of waging small-scale war against modernity.

I think realism and illusionism still have great artistic potential because reality is still something we find difficult and threatening. I think Ayn Rand said that people can avoid facing reality, but they can’t avoid the consequences of not facing reality. I think my work is very much bound up with these issues; with naturalism at one remove, with fantasy and disillusionment. In our culture, to an historically unprecedented extent, affluence and industrial might have become weapons in a general war against reality, against nature. You know what? Nature’s going to win!

Tell us a little bit about your palette. It seems to be on the darker side, but you also employ very rich and vivid hues. Looking through your work, we seem to get the sense that it’s the evening–or a time when natural light is dimming but artificial light is not yet necessary–does that make any sense? Is that something you’re attracted to?

If I was a pianist I think I’d want to be Chopin or Lizst: I want to use ALL the notes. There’s usually some spot in my paintings that approaches absolute white, and an area that is as black as I can make it, lots of neutrals but also some pure saturated colour, often an orange or red or blue. Most of the paint actually consists of earth colours, black and white, but when I want a pure colour I’ll use the purest pigment I can find. And since I’m practicing good old-fashioned chiaroscuro the general tone of the pictures isn’t very bright: there’s no way of making the highest lights read as lights except by subduing the general tone. Lux in tenebris…

Leonardo said evening light is most beautiful because it softens objects, makes them appear to glow mysteriously, and I think he’s right. But perhaps, for our civilization, it IS evening time. I’m reading ‘The Decline of the West’ at the moment…

Your subject matter really runs the gamut, from the classic kitchen and market type still lifes, to more cabinet of curiosity types–sometimes including carefully placed modern features, like the deflated blow-up globe in “It’s the End of the World as We Know It” (are you by chance an R.E.M. fan?) and the plastic bags in “Veiled” (this is one of our favorites). Even Roman-style portrait busts make an appearance. How do you choose your subject matter? Do you play around with one grouping of objects for a while or do you know what you want to include right away?

No, I’m not an REM fan but I like to stay close to the vernacular. Finding the right title can be very important: if I can use a title drawn from popular culture, and it’s appropriate, it can ease access to what is often a rather complex and involved allegory. My subject matter is selected and arranged in attempts to make meaning. Beauty is very much a secondary concern, as is ‘purity’ (I’m not afraid of kitch). Early on I used busts and life-masks as ways of importing a human presence into the pictures. At the moment, with three small children around, lots of toys and model dinosaurs end up in the work. I find this a natural development: children’s toys are essentially heuristic and microcosmic, and suit my purposes perfectly. And there’s no better vanitas symbol than a dinosaur!

I’ve recently gained access to the collection of the Natural History Museum in Dublin, a veritable Aladdin’s cave of ‘dead nature’ to exploit. I’ve started off with some paintings of extinct animals that fitted with my ‘vanitas’ concerns, like the dodo and ‘Megaloceros’, of a great Irish elk skull, which is my largest still life so far (36″ x 72″).

Watching my children build enormous towers out of wooden blocks and then destroying with such casual indifference was the starting point for ‘I’m Still Standing (Yeah Yeah Yeah)’. Seeing their towers collapse I couldn’t help but be reminded of other collapsing towers. It seemed the perfect motif for a vanitas painting – a meditation on mortality and the fragility of our grandest endeavours. The background with aeroplane is intended to be just sufficient to trigger those 9/11 memories, but to me, the tower stands for the fragility and transience of everything human, which is why I called it ‘I’m Still Standing’. As a painter, I think of it as a self-portrait: “Look at me! Look at my beautiful bright colours and how grand I am! Yes, I’m a bit wobbly and fragile and I know my fate, but (for now) I’m still standing…”

Do you actually set the objects down in front of you and paint them? Is it challenging to work with perishable materials? Where do you find your materials?

The painting is usually placed right beside the objects so I can paint them life-size and as convincingly as possible. Perishable goods are a problem but I usually paint them early in the process. They often end up replaced half-way through. In any case, at a certain point the picture ‘takes off’ and I become less dependent on copying reality: what the picture needs becomes internally obvious.

As we acknowledged before, your catalog of work is so vast, where does your still life work fit in? Did you start with still life? Did it come later? Do you see still life as a sort of technical practice or a way of working out techniques or ideas (we were reading some academic writing on the genre and the author posited this question)?

I suppose fundamentally I think of myself as at odds with the genre and most of its ‘default settings’. But in some ways it’s a good position to be in: everything I do in still life is done tactically, strategically, self-consciously; my dissatisfaction with and to some extent contempt for the genre is what allows me to push it around, to use it purely as a means to my ends. Every once-in-a-while I get very frustrated with painting objects and feel like I’m close to exhausting its possibilities for me, but it usually doesn’t last long. Right now I’m flying along. It’s a great time to be a Cultural Pessimist!