Marian Fountain is a New Zealand sculptor who has lived in Paris for 22 years and returns regularly to the country of her birth. Melding the inspiration of the rich diversity of European art, history and culture with her New Zealand roots and the cultures of the Pacific, Fountain uses the female form, plant life and the animal kingdom, often in states of metamorphosis, to explore themes of fertility, conflict, change and growth.

+ + +

Your biography and your body of work are fascinating. You’ve lived and exhibited in a number of places. Where you currently live in Paris, what kind of studio do you have? What is your work space like?

It’s an ‘atelier d’artiste de la Ville de Paris’ (social housing for artists). I moved here in 2008. Since 1991 I had been officially squatting two locations that were waiting for demolition or building permits : for the first eight years in a little house built in 1900 in Montmartre with no bathroom and an outside toilet, conditions were very ‘bohème’ but the garden cascaded down three terraces to the Bateau Lavoir at the bottom. The little house felt like the Grandma of Paris so I had an open-door policy and met Parisians that way.

For the next eight years I lived in a 400m2 factory space in the centre of Paris, and there too it was open door with people using the downstairs area for theatre, music and various courses. In 2000 we held ‘Picnicart’ parties every month where people bought their own food and five or six artists exhibited.

I am happy now to have my own workshop and living space with a garden at the end of a grassy courtyard. It has been extremely lucky to be able to work outside and to have had three gardens and sky in Paris.

You attended the Elam School of Fine Arts. Describe your very first experiences with bronze casting.

It was actually a piece of wood that introduced me to the foundry. I was in my second year at art school and the first year specialising in design and sculpture. In the wood workshop on the first floor, a small piece of wood I was trying to mill shot out of its clamp and nearly took my stomach out on its fast trajectory towards the window, which luckily was open. Rather shaken, I went outside to look for the wood and came across David Reid, who ran the foundry in the courtyard. Then and there he started showing me the process of simply burying polystyrene and pouring metal into it : the simplest of molds/casts. I was immediately hooked. Somehow it seemed to me a more ‘balanced’ process than the violent machines often used to manipulate wood. And it seemed you could create something from scratch.

How did you get the opportunity to go to Italy and receive training at the Rome Mint? And how did living in Rome suit you as an artist, and as a person?

I’ve been involved with the British Art Medal Society since 1984, attending weekends most years which provide a fantastic opportunity to visit museums with curators, around the UK and on the continent. During an international congress (FIDEM) dinner in 1984 in Stockholm, I met the person in charge of medals at FAO in Rome, who helped me apply for the school at the Rome Mint. There were no fees but I plunged into Roman life, earning my own living and also making enough work to exhibit in a gallery on the Spanish Steps. I was involved with a familly who cast sculptures in their foundry on the seventh floor of the medieval tower where they lived.

It was fantastic to have first-hand experience of the artistic and artisanal traditions in Italy.

Mark Stocker (in the magazine Art New Zealand discusses your sculpture series, Remote Control, how your work highlights the evolution throughout history of objects of command, from Maori rakau whakapapa (used as mnemonic aids to Maori elders reciting long genealogical histories) all the way through to today’s hand-held remote controls. Your work thus seeks to bridge time, a sense of touch shared with our ancestors. In your sculpture work, do you channel ancient traditions such as these in a conscious way, or is this the unconscious/subconscious at work?Yes, it’s a thrill when sculpting to feel in touch with the artisan ancestors by repeating exactly the same manual gestures, understanding better the many artifacts from the plethora of cultures and eras. Through practice, the hand-eye coordination blends the conscious and the unconscious, and we begin to feel part of the collective lake of consciousness.

I feel that creating things with the hands is like keeping the sap flowing through the branches and roots of a plant, keeping the organism (myself and the collective consciousness) alive and healthy.

It’s interesting how our relationship towards touch and form is forever evolving – when we touch the now miniaturised objects of our personal technology, even the buttons have disappeared completely. Before we had a manual task to do while commanding our daily lives, like pressing a button or dialling a number. Now our brain is being wired differently.

What sculptural materials are your favorites to work with? Have you ever worked with unusual, even completely out-of-the-ordinary, materials?

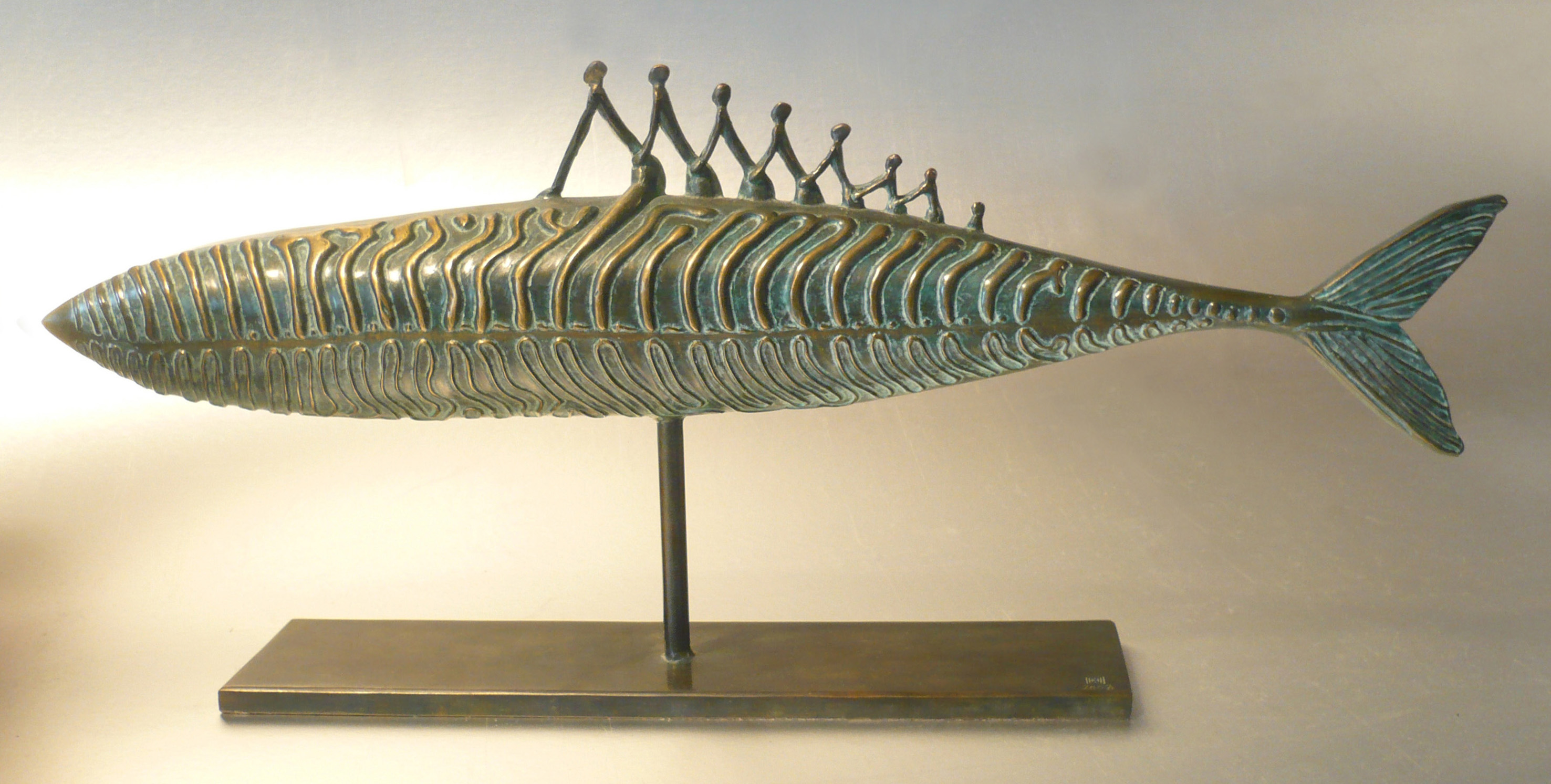

Bronze is a material which has a rich history in many cultures through time. Making sculptures from it seems to bridge time, informing us at once of our present and our distant ancestral past, and emphasizing that the present is but a notch in time.

To make a bronze sculpture the process means that I mainly work with plasticine, wax and plaster. They are natural materials which are pleasing to manipulate, not toxic, and furthermore the negative and positive steps in moldmaking add more stages in which to intervene, building up a situation of many creative possibilities.

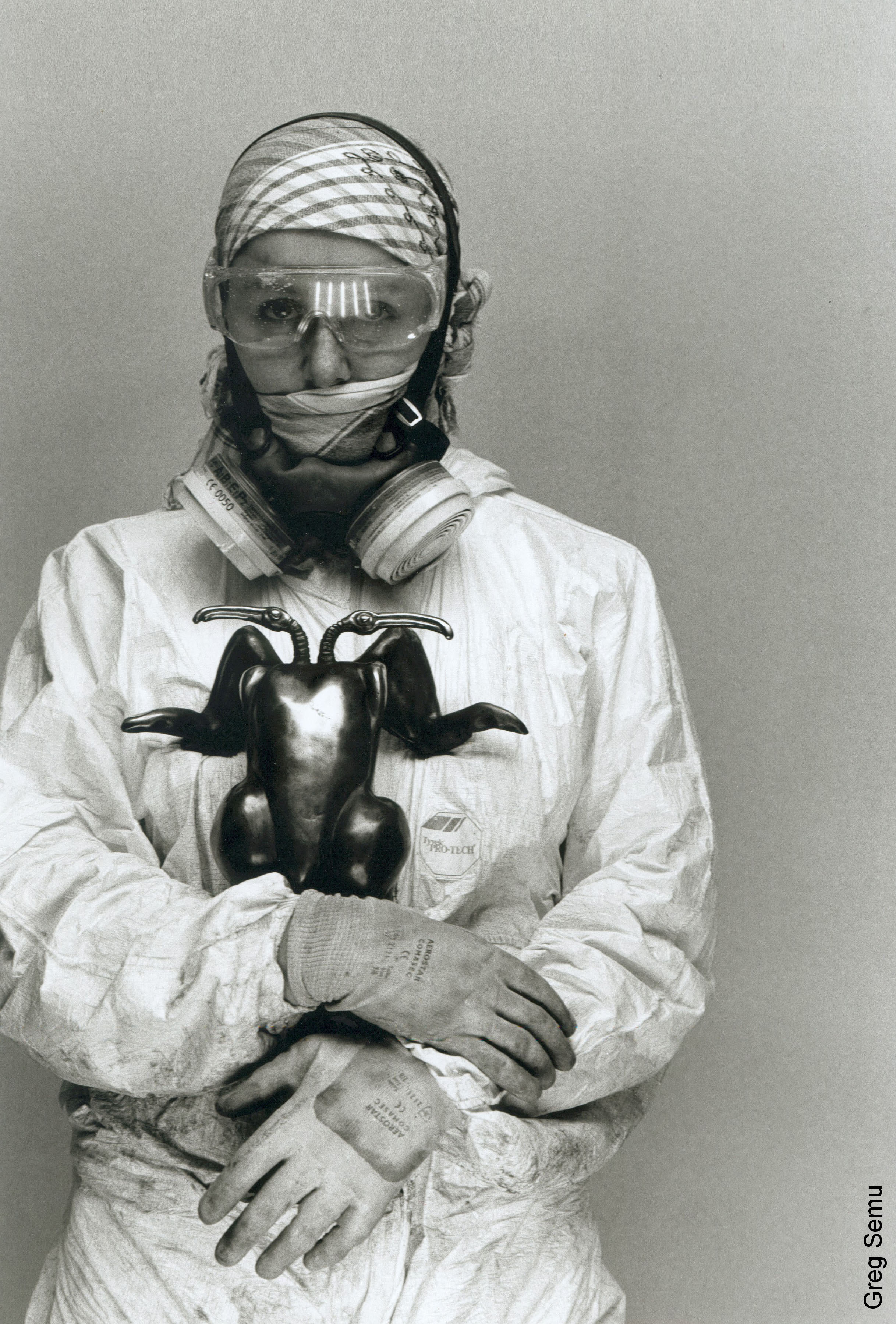

One series of sculptures started from molding an animal or plant from the market, which we then ate amongst friends. It would have been a shame to throw the rabbit or the fish away after molding it, and to eat it felt like we were dispelling the taboo of manipulating meat in such a way, or ‘playing with one’s food’. I remember all of those meals vividly.

‘Love me’ was made out of plaster covered with fur, but I got a taxidermist to do that. It was a challenge for him because usually he started with the skin or fur ‘suit’ within which he made the shape of the appropriate animal, whereas this was the other way around.

Most people who major in archaeology don’t have a background in metal sculpture. Have you worked with archaeologists in your career, or would you like to?

During my exhibition at the Museo Arceologico e Numismatico in 1989 I felt extremely honoured to be exhibiting in the same room as the Etruscans. I presented the pieces as though they were the first discoveries from an unknown culture, and a lot of the objects had question marks concerning their use.

I am interested in having more interchange with museum historians than perhaps with archeologists, who are in the business of finding things. In museums the objects have already been found. There are more opportunities now to collaborate with museums as they are finding new ways to approach and interact with objects from the past.

What do you enjoy doing when you are not creating art?

Music and cooking. Creating a song or a meal are different processes of crafting: adding and eliminating, building up layers of texture.

What are some of the projects or works you are currently focusing on?

‘Island Timer’ highlights a recent interest in transforming archaic sculptural forms, giving them another relevance for today. She is a statue of the Cycladic island civilisation, but her frontal gaze is distracted after 4000 years, she is no longer looking straight into the future. What’s going on? she seems to be asking. Something has changed. We see that she is now up to her knees in water…and on the reverse her tattoos tell us that time is running out.