I reach for the bottle and my mother quacks in protest. I try to tilt it so I can drink without my lips touching the glass. The wine is warm and fizzy, acidic and sweet. It reminds me of sick.

Featured Writer

Featured Artist

Writers

The Green and the Blue

by E.A. Fow

When you fly over the North Island and its peninsulas and the small islands that swim beside it like green fish, you think, “Oh how beautiful!” but then you land, and you’re so taken in by the loveliness, and the clarity of the light, and the plethora of new, saturated colors, and the warmth the people have for complete strangers, that you don’t notice that the landscape is seeping into you. The green surrounds you, pulsing behind everything else, and you’re breathing the pollen, and the trees and plants; they flourish inside of you. And that’s just in Auckland, the most concreted-over part of the whole place.

Fantastic

by Vaughan Rapatahana

Fuckin’ strange country we all inhabit here eh. White man hires a brown man to whack another brown man black ‘n’ blue. First brown man goes to Paremoremo for a long apprenticeship session to sharpen his skills in dumb cunt violence so he can keep up the trade even better when he gets out. White prick goes to Borstal type holiday camp down country so that he can continue to be a complete arsehole when he gets off after two months through ‘good behaviour.’ Fed and clothed and exercised. Just what we all need.

And all paid for by the taxpayers, ‘cept they wouldn’t even know just what was going on in this dystopian universe so remote from their rotary lawnmowers, Tupperware gambols, PTA meetings and battened batches down the beach.

Oliver and the American Girl

by Amanda McRaven

The roads are prolonged and straight out to the coast. He drives them with drunken effortlessness. What you are still not used to is the darkness. No cars, no street lights, a far-off homestead with one tiny porch light, and then just stars. Even the quietest, darkest parts of America are not this dark.

The land smooths out as if it were ironed by a stolid Kiwi farmwife, and the beach towns spill out of the stretching expanse. The moon is huge. The matches are difficult to find. You can no longer recall if first you swam or lit the driftwood fire, or fell into star-exploding sex. But it all happened.

The Willow Tree

by Melanie Dixon

Her bedroom is still the same as it was before. My father tells me not to go in there, not to touch her things. But sometimes I see him sitting on her bed, hugging her favourite bear, the patchwork one with green button eyes. Sometimes I see my mother sitting under the willow tree and gazing up into the branches to where the tree-house used to be. To where she laughed for the last time.

A pair of hands

by Airini Beautrais

He liked to drink two cups of tea, the second stronger than the first, while he read the front page of the paper and the classifieds. The situations vacant were few and unpromising. In those days, the days of raw sewage, the main street was flecked with empty shops, dust crusting their windows. At the end of the river the downgraded, dying port sat like a scab, silting up, sealing the town’s former exit. In the local factories, machines came to a final halt. Business shuffled elsewhere. Richard would close the paper with a sigh most days, and set out for his morning walk; to look at the water, to see what the town had coughed up.

In the Rain

by Tom McLean

These are the things that happened today in Wellington, in the rain: The wind from the harbour moved the curtains and touched the hairs of my arm with insistent promise, and the rain came into the street at a fighter-pilot angle. I stood on the overbridge that goes over the motorway from the Terrace and turned my face into the wind so that the rain lashed at my face like a solid thing.

To a false friend

by Gail Ingram

Imagine in your rambling you stumble over a dead sheep. Not only dead but full of

maggots. What do you feel — pity or revulsion?

See, pity is for the moment of death. It changes when the decay sets in with its

curling stench and squirming scavengers.

And yet when you return much later, you see shining white bones and the odd

tuft of wool caught on bent grass—inoffensive signs that something once lived;

nothing to raise your bile.

But perhaps you find the analogy for our dead friendship too harsh — too grisly

a comparison?

Sleeping on a Story

by Gail Ingram

The story is lumpy, many small hillocks under the white sheet that’s really a foot kicking my liver and pain shooting to the base of my brain, what’s that called again…the hypothalamus? Tonight, there was a room full of children all wanting their voices to be heard, a theme I keep coming back to, the small boy with the brown face from Egypt or was it Oman?

Diminishing

by Nod Ghosh

On Friday, we found your gall bladder in the bath, a shimmering purse of an object, olive green, nestling in the plughole. You told me to leave there, that you would attend to it after breakfast. You refused the bacon I’d grilled, but happily ate eggs and toast.

By the following weekend, I discovered your pancreas by the piano, pale pink, looking like it would crawl off under its own steam if poked with a stick. I wasn’t sure what it was at first, and was alarmed when you said something about having dropped it on the way to the laundry.

Hartington

by Nod Ghosh

George Hartington strides with a menacing tap of silver tipped cane on cracked paving. Tip-ting-tap. The resonance of one unnecessarily hard tap sends a shiver of sensation through him, nine volts of warning. He feels the strain of desire, a small but irritating dog in the mind of his lower body. A dog that yaps incessantly, demanding satisfaction.

The Wolf Runs out of Tears.

by Nod Ghosh

Once I watched in cold fascination, as you gave birth to another delusion. Converted an innocent intimate liaison into an assassination. Somehow I got the feeling I’d seen it before. Then I remembered I had; yet you told it like it was a revelation.

You Look Beautiful when you Smile

by Celia Coyne

Ever since Happiness heard your name, he has been running through the streets trying to find you. He saw you on a sunny morning, striding down Mount Pleasant, slowing only to avoid the spongy tarmac where a burst pipe was sending water to the surface. You were moving fast, your head held high, taking in the view over Christchurch to the mountains beyond. The air was clear with the occasional whisp of fragrance from the autumn-flowering shrubs. Happiness almost caught up with you, but you gave him the slip at the bottom of the hill, stepping neatly over the bricks where the path had unzipped. He was left standing at the side of the road, waiting for a gap in the traffic.

One Beautiful Step

by Michalia Arathimos

When I told Simon I was going south to grow persimmons he made some kind of wordy joke, some sort of joke like he likes to make where he rolls words around. It annoys most people. Because, I said, it made complete sense, going south. And growing persimmons. Why not? Why bloody not? And so he said. And so I said, and we were boozed by then, I said well I plan to surpass all my own expectations, I plan to climb that mountain, I plan to conquer the mountain of persimmons and we were very drunk by then I remember, on not-inexpensive champagne. We were in the business district and he said I do hope this venture is persimount to your current success in the business world and I cracked up. I mean, it’s not even funny. But I do really do love Simon, you know. He’s a stupid son-of-a-bitch.

Repco

by Holly Painter

I go, ‘Yeah, mate, she’s hot.’

‘Nah, she’s not hot. She’s gorgeous, bro. Fuckin smoking. I gotta have this woman. I love her already.’

‘Alright,’ I say, ‘then go get her.’ And I point to the caption. Says her name’s Emily and she’ll be at the Samsung Miss Hamilton comp at the V8 supercars in April. ‘You can have this woman, bro. You just gotta go to the Hamilton V8s and find her.’

Seth looked at me like I’d proposed a trip to the bloody moon. ‘Nah bro, it doesn’t work like that.’

‘Why not bro? Anyplace else in the world, you see a beautiful girl in a magazine, you’d never have a chance of finding her, never get to talk to her. But in this glorious country of ours, they come right out and tell you where she’ll be, and afterward, she’ll be wanting blokes like us to buy her drinks. It’s brilliant.’

First Love

by Terence Rissetto

On overcast days she loved watching the pukekos

Their white tails flashing and bobbing like the tutus

She used to wear when she danced

As they searched beside the motorway

For their own hidden delicacies

He gave her a necklace of 2 severed pukeko legs

That crossed and uncrossed as she walked

That she hung over her bed at night

And put on again in the morning.

Fork n hell

by Terence Rissetto

Fork off you little cutlery

Someone yelled out

Forkinetically she didn’t seem to hear it

And speared me a warm smile

She had enough on her plate

I gave the old forks the fingers

You could have cut the air with a knife.

I’m a better fork than she is, one said

What do you fork n see in her? She desserts better.

It was a knife in the back

Forket it I said you’ll never be as knife and sweet as she is

Dark Mousse

by Terence Rissetto

My mousse is upset with me.

She sits by the table with crossed arms and frown,

staring cold chocolate frostings of sprinkled icings

with a hint of blackcurrant.

I suspect she is an undiagnosed passive/aggressive.

I have sacrificed my all to please her

Stirred, whipped, blended, folded, creamed, licked, kneaded

But she remains indifferent, aloof, my own little noir mousse Venus in furs.

the mouth of rain

by Kerrin P. Sharpe

she takes the blood pressure

of the forest/ and hears

her mother breathe the hug-me-tight

stitches/ of kauri and macrocarpa/

her mother so tongue-tied/

she could coax ships into the harbour/

and the southerly straight out of it/

her mother once famous for the tricks

of her breath/ could play a sheet

of corrugated iron like bagpipes/

and make her carving knife sigh/

these forest nights/ her mother

breathes for all of us

In the tradition his day reduces

by Kerrin P. Sharpe

the hunter wears wolf teeth and

kneels by hospital beds. he

regularly walks where deer play.

he drowns their sons and

packs their mouths with grass.

the Chatham Islands pray for him.

he leaves his boots at the door

of the fish house and collects

tongues from the lace lips

of salmon. he hooks their

song with the deep

pigment of night this is how he

turns the light.

her hotel is staying in Oriental Bay

by Kerrin P. Sharpe

and her surgeon leaves stirrups

obstetric forceps and his axe

in the bath now the sardine

must be buried she no longer

hears the conversation of street lamps

instead everything that began in water

from the ash cross

on her tiny metallic forehead

to the white oil of her empty belly

becomes the silver of dust

that most mornings

bows to a long slow car

The Autistic Child Considered as a Nimbostratus

by Siobhan Harvey

Film in black and white.

No fancy technique. Keep direction straight.

Shoot as if a deep, obsidian lake

which looked at long enough reveals

a mother and child, small as ice-pellets, settled at its edge.

The Gifted Child’s Creation Story

by Siobhan Harvey

1 In the Beginning

He reads Genesis dreams the world

a closed eye, a cloud

an unborn asleep in a dark place

light arriving at birth.

Considering a Cloud, a Bird, and a Poem

by Siobhan Harvey

Sense the ways poems search the earth

for knowledge of how, like birds

and clouds learning to fly, the word

first formed in air. Together

a cloud, a bird and a poem are considered

with such shape and symmetry as stretch

songs over bone and sky, such colour and vision

as remember the first poem, and all poems since.

Considering an Oriole and a Bird Extinct

by Siobhan Harvey

Excavating a poem is like excavating a dead bird:

for both, we must count the silences, unravel

the subtext and discover how order is broken

across the body, spilling into fresh lines.

And even when they fly against the trees in bright formation

You know the peace they brought was long overdue.

An island upbringing

by Kirsten Le Harivel

The anemone is burgundy fronds

and bulbous belly suctioned onto

charcoal-coloured rocks. The sky

is grey and soft and spittles silver.

Wind pumices the skin of faces

huddled in anoraks. Necks crane

out for a sandwich spot and with

luck, a gentle flicker of sun.

Pluck

by Kirsten Le Harivel

The summer you left

I picked cherries,

kilos of plum-sized fruits

filled my puku, sometimes

the berry bucket. We spoke

in the paddock

after dark

I heard couplings

their arousal silhouetted

the whitebait are running

by Kirsten Le Harivel

reclined against

the bank

the copper curve

of your neck gleams

I bob my chin

to your raised arm

keep turning

my mind in water

your waders

grazing my ankles

Writing Conversations

by Kirsten Le Harivel

A man and a woman live in a house. On her birthday he presents her with the Complete Oxford Dictionary. It looks like a Bible. There are so many words she needs a magnifying glass to read them. Am I folliculated? Am I a sac, or a small secretory cavity filling myself with the litter of others? The woman laughs with her wavy auburn hair. Turns to her husband, What do you think? He has his head stuck in a screen of small letters. Check this out, Bolt just won the 200m. Wow! What is it about those Jamaicans?

Looking for Hinemoa

by Jon Wesick

Round speed-limit signs, one-lane bridges, driving mountain roads

on the left, windshield wipers when I reach for turn signals,

Cherry blossoms, Southern Alps rock and ice,

fern trees, red tussock, granite scoured by glaciers,

the chill turquoise water of the Tasman Sea, black swans,

pukeko birds, quail, red-billed seagulls, ducks

with sergeant’s stripes, tree avalanches, waterfalls, the tui

that knocked himself silly flying into my picture window,

dirty blue ice melting into gray runoff from the Franz Josef Glacier,

Lambs gambol while sheep fatten for the slaughter.

The Tree House

by Kate Larkindale

My voice came back from wherever it had been hiding and I screamed, a ragged sound that shattered the peace of the night. I heard scrambling from above me and looked up to see Luke peering down at me, his eyes wide and frightened.

“Oh, Jesus!” he breathed. “Danny! Guys! Come quickly!” He leaped down from the tree and was by my side in a second. The moon was swept behind a cloud again, plunging us into oppressive darkness.

“Danny!” Luke cried again. “Get down here. Now!” Tears ran down my face, pooling in my ears and trickling down my neck under the collar of my t-shirt. I could hear a strange moaning sound and realized it was me. Luke lifted my head so it rested on his knees, his hand huge and gentle on my head as he stroked my hair.

A Right Dag

by Carolyn Stack

Jack wasn’t feeling very entertaining on November 5, 1956. He drove his carpentry van down the Esplanade — the main street in his small town, Kaikoura — and turned into his driveway at precisely 5 o’clock. As he scuttled back up the gravel drive toward the street he heard the back door of the house open. The plump figure of his wife, Irene, in a bluish house-dress (like a bruise, he thought) appeared on the steps: “You be home by six,” she called out. “The kids are relying on you to light the bonfire.” He waved an arm in her direction, batting her away. Fix the window in the lav; take the kids out for once; lay off the booze. Jack had laid down his life for his country and this is what he got in return?

The Nocturnal Florist

by Lucy Butler

In your wide-eyed wake I’ll be walking dark streets, burying my face in flowers. Leaning over fences, nuzzling inscrutable night-colours, my head lolling on its stem like a too-heavy bloom.

Perhaps it isn’t fair to take myself out on other people’s flowers; it is a grey area, etiquette-wise.

Getting Schooled

by Claire Orchard

Upon arrival the teacher surveys the field: one five year old in retreat within the anonymity of a cubicle, the other, round faced, mouth a perfect open o, looking up at me from his position beside the sink. Were you fighting? No, we weren’t. His eyes are round too, and glossy with the righteous light of truth. We weren’t fighting. We were just deciding who’s the boss.

Growing up in Waiouru

by Claire Orchard

That was summer. Winter, we put on shoes and stayed closer to home, where the chippy in the kitchen was always on. At night the thermometer in the hall gave up caring where the mercury should be and hunkered down like the rest of us in that thin-walled house of bare wooden floors. When the wind blew in off that mountain and dropped the temperature real low, we’d fight over who got Zeb the dog for the night. Poor Zeb would look from one of us whistling, finger-clicking kids to another, overwhelmed by the sudden enthusiasm for his company.

Four Stubbies

by Zoë Meager

Six thousand houses and one magpie lost power that day, all from the joining of two things never meant to be joined. The only ones to hear it were a mob of cattle, which took off at a run, she said. She’d watched them, washing like a wave down the paddock, churning up the snow, surf on a beach, and she wondered at the cause of their dreamlike wading. It wasn’t feeding time.

Tsunami

by Diane Andrews

This glacier is high on the mountain but swings through a steep curve to quickly reach a low altitude. This is what has given it its peculiarity — of shrinking and growing in an endless seesaw that mirrors the phases of the moon. When Tasman Glacier retreats she rapidly heats and dumps her black pebble cloak like a stripper discarding a corset. When she decides to march towards the plains below she shovels her unwanted stones in front of her like a giant bulldozer.

At the point where she stops, when the chilly air warms up and she melts a little and flops and slithers in a watery pile, a dam wall is built up. Over time her feet permanently dangle in a flat opaque expanse of milky water tinged with apple green.

Glacial Karma

by Julie Maclean

Bodies with limbs like twigs could have been poking out of the snow. Marooned in the remote, we were black ice, white knuckles away from that. We listened to windows splintering under hundred mile an hour spleen, bus heaving its warning. We felt plates shifting in glacial memory, or was it humour.

The Cure

by Sandi Sartorelli

I suffer from radiator illness, and now I cough at night. Phlegm sings descant in the lungs. The bloom in my adrenal iris slot has faded. I want to be healed, get back on the horse so to speak. Sit high on the stud, be a stallion’s rider.

Those Flipping Refugees Will Not Catch On

by Sandi Sartorelli

Clouds diffuse light like a Himalayan salt-lamp. Listen it’s the sound of death — relentless tyres in both directions. After a time, rain begins to darken the asphalt, but a family remains. A large blue mother leads her babies in tentative steps of wellbeing. They wait like the chicken who dreams of the other side. Road safety was not a concern when only birds lived on this land.

Suffer

by Bruce Curtis

I am there now

Those places

Where it happened

It happened

It happened but not to me

A moth flutters

Wings on a windowsill

Layers

by Bruce Curtis

Booted up

In the Avon loop

A number 2

With the Avon loopies

Always grey

Always cold

That Christchurch cold

Five layers deep

From gabardine to singlet

Daddy

by Bruce Curtis

Footprints in the sand

Along the Canterbury Bight

And there 19

51 you buried beer

Pines Beach

Jim and Colin and Ish

And there 19

81 I hassled bouncers

North Brighton Surf Club

Took acid

And paddled

Lizard and Ian and Tips

And you?

Isaac Van Amburgh meets the Queen

by Jeni Curtis

His hair curls, soft and black, and he swaggers with the air of a Sicilian brigand. He brandishes his whip to make us cower in fear. But we know better. We, who have travelled with him, from America to Britain, we have fame through Isaac. We are the beasts the public come to see. We snarl and roar and bare our teeth and seem to give obeisance. One leap, one concerted action, and he’d be gone. The audience knows it and they wait.

Walter Rothschild’s Zoological Museum

by Jeni Curtis

Some of us were lucky. We escaped the slaughter, herded up on those sun-filled plains and shipped to this soggy country. The food was better though, no fear of predators, and interesting neighbours. We mixed with spiny anteater and pangolin, deer and wild asses, capybara, and of course the giant tortoise that he rode. And Walter liked his flightless birds, kiwi, emu, rhea and cassowary. He liked to eat their eggs, said they were excellent food, especially scrambled and in omelettes and cakes. All in the name of science.

Mrs N

by Jeni Curtis

I always thought it sad the way I came to be remembered. In the Mystery plays I was a fat wimpled harridan, an object of mirth to those in the street, who hurled abuse and cabbages. Later I became a round wooden doll with a peg head who stood stolidly by her round wooden husband and the pairs of elephants, giraffes and camels on the deck of an undersized boat. We were lucky if we weren’t lost down cracks in the floorboards of the nursery.

Artists

Interviews

Interview with Sarah Bainbridge

Retrospectively I think whatever job I’ve had it’s been the narrative aspects that I’ve enjoyed the most. I was an SPCA inspector for a couple of years. It was all about investigating complaints of animal cruelty, which we would characterize into ‘skinny dog’, ‘dog on chain’ etc., but there was always a story behind their predicament that revolved around their owner. It didn’t excuse what happened with the animal, but I just found it interesting. Today I scan hearts, but alongside the echo findings it’s learning the person’s history and symptoms and then following the progression of their heart condition and treatment that is fascinating and endlessly variable.

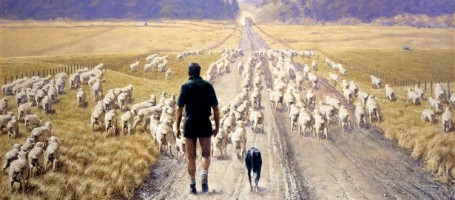

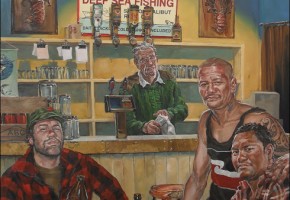

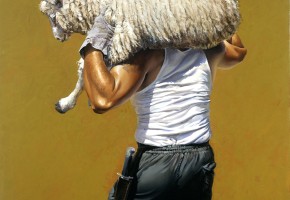

Interview with Barry Ross Smith

It is hard to justify something as ridiculous and as old as painting is; it’s so redundant in today’s society, superfluous even with the plethora of images saturating our everyday vision. To connect to others through being disconnected and alone in a studio seems almost anti-technological in this interconnected age. Perhaps this space and time that the artist creates poring over a work is what also creates the space for a viewer to become quiet, to contemplate and reflect. Whatever it is, I believe that painting still holds up against all of its successors. I find painting to be the most direct, expressionistic, authentic and responsive medium for a subjective communication. It is the result of the interconnectivity of the hand, the eye and the canvas; the manifestation of these things – interacting. Paint on the end of a brush shaped by the subtle movements of the hand and decisions of the eye is a complex, idiosyncratic signature.

Interview with Holly Painter

In the US, if you see an attractive or intriguing person in a magazine or on television, he or she stays on the other side of that media divide.

But New Zealand is so small and interconnected that Kiwis are rarely more than two or three degrees apart, and the line between “world-famous-in-New-Zealand” and normal person, or between knockout beauty and Average Joe from Ashburton, is much more permeable. And that’s interesting because it levels the playing field somewhat, and an unusual kind of social mobility is possible. But while it’s freeing in the sense that it enables relationships between people you might not expect, it also means you have fewer excuses for not trying.